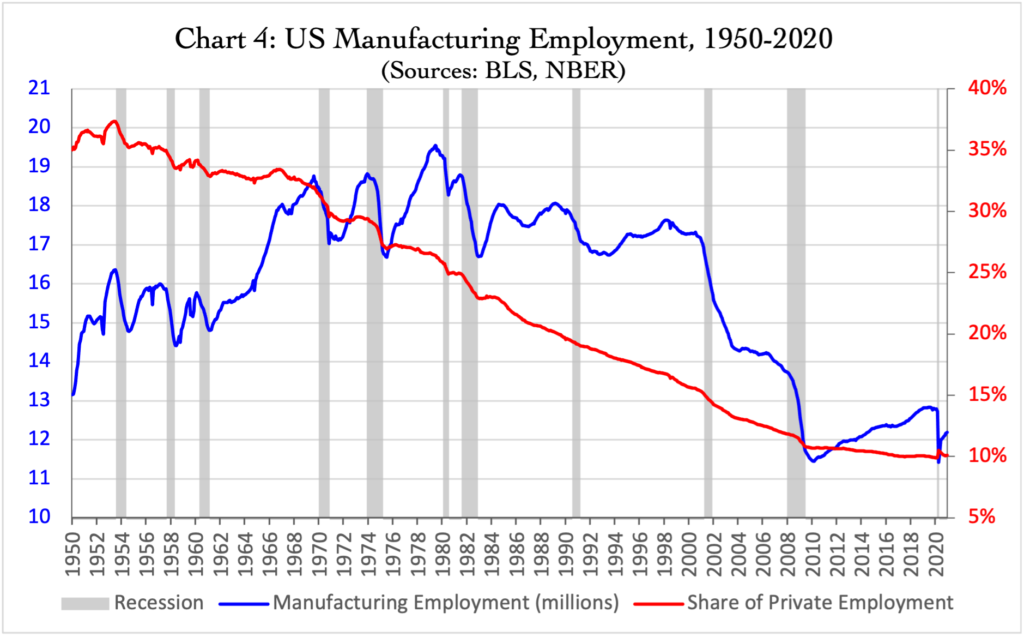

Key Takeaways From Chart 4 and Commentary

- From a peak of 19.5 million jobs in 1979, manufacturing declined by 38% to 12.2 million at the end of 2020.

- As a share of private employment, manufacturing declined from more than 33% during the 1950s and 1960s, to just 10% in 2020.

- Cyclical declines during the 1980s and 1990s became secular in the early 2000s.

- Every one of the 19 industries within the manufacturing sector (defined by the BEA) employs fewer people in 2020 than it did in 2000.

- The withering of the US manufacturing sector is the single most important factor in America’s weakening economic performance over the last four-plus decades working through its effects on productivity and employment (the key drivers of per capita GDP growth as shown in Chart 2).

- After illustrating its impacts on productivity and employment, I will examine some second-order effects, including declining rates of investment, deficient US saving, chronic trade deficits, and asset price boom and bust cycles.

- I will then evaluate the misleading explanations for manufacturing’s decline offered by the punditry.

- The next several charts will analyze the productivity drag caused by manufacturing’s decline.

Commentary

The manufacturing sector was once the foundation of US private employment. At its peak share in the early 1950s, 37 of every 100 US private sector workers were employed in manufacturing. Although that share declined somewhat in the mid and latter 1950s, it held steady throughout most of the 1960s around 33% as nearly four million new manufacturing jobs were added amidst a growing labor force and strong economic growth. On net, the US economy continued to add manufacturing jobs through the 1970s, reaching its peak in absolute numbers in 1979 at more than 19.5 million jobs. Thereafter, the manufacturing workforce began to shrink over the course of each business cycle until falling precipitously in the first decade of the new millennium. At the end of 2020, manufacturing represents just 10% of private sector employment and employs about 12 million people.

From the peak, the losses at first exhibited a cyclical pattern. Coincident with every US recession, weakening domestic demand produced large manufacturing employment declines. But in the expansions that followed, domestic employment weakness continued, never fully recovering its previous losses. Then the attrition went from bad to worse. Starting in 1998 the manufacturing sector began to shed jobs even during economic expansions. Though some were recovered in the years that followed the global financial crisis, employment fell once again with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and has yet to recover its pre-pandemic peak.

No part of the manufacturing sector was spared in this decline. The relentless annual declines that previously characterized only certain labor-intensive industries within manufacturing, such as apparel & leather products and textile products spread through most of the sector. Every one of the 19 industries that comprise the manufacturing sector (per the BEA) employed fewer people at the end of 2020 than it did in 2000. Even the more advanced industries where one might have assumed the US had some technological advantage have suffered large losses. Machinery, for example, has shed over 400 thousand jobs since 2000, representing 28% of its workforce, while electrical equipment has lost more than 200 thousand jobs – 36% of its labor force.

Most Americans are acutely aware that US manufacturing is no longer the powerhouse that it once was and many have been directly affected by job losses among family and friends. But the analyses emanating from the economic punditry have generally minimized – or dismissed completely – the impacts of this structural change for the health of the US economy. I will defer an analysis of the causes of manufacturing’s decline to later posts.

My initial focus in coming posts is to first explain its negative economic consequences for the US economy. In the charts and posts that immediately follow, I will show that the withering of the manufacturing sector is the single most important factor in America’s weakening economic performance over the last four-plus decades working through its effects on productivity and employment – identified in Chart 2 at the two key drags on the growth rate of GDP per capita. After explaining these first-order effects, I will then consider some seemingly unrelated second-order consequences, including the drag on investment and saving, chronic trade deficits, and the cycle of asset bubbles and busts experienced over the last several decades. The next several charts will illustrate the productivity drag caused by manufacturing’s decline.