Key Takeaways from Chart 7 and Commentary

- The shift of labor resources out of the high-productivity growth manufacturing sector and into a variety of lower-productivity growth services industries subtracted 0.90% on average from annual US productivity growth between 1980 and 2009.

- While reported productivity contributions from the financial sector in the 1990s and 2000s appeared to offset some of these declines, those contributions reflected nothing more than its efficiency in churning out worthless securities to fuel an old-fashioned credit boom, which ultimately generated a massive housing bubble and consumption binge that brought on the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

- The collapse of manufacturing productivity growth after the GFC revealed the transitory impact of productivity gains achieved during the global labor arbitrage frenzy of the 2000s; US producers traded away the sustained future gains that come from capital investments, process improvements, and learning-by-doing to the foreign firms doing the actual manufacturing.

- US policymakers deliberately traded away the primary engine of long-term productivity growth – the US manufacturing sector – and the American people got only a shrinking middle class, financial crises, and an aggressive geopolitical competitor in China, in the bargain.

- It would be hard to conceive of a set of policy choices more destructive to America’s economic health, unity, and national security. That these policies flowed directly from the worldview that animates much of the Washington establishment indicates an urgent need to rethink American grand strategy.

Introduction

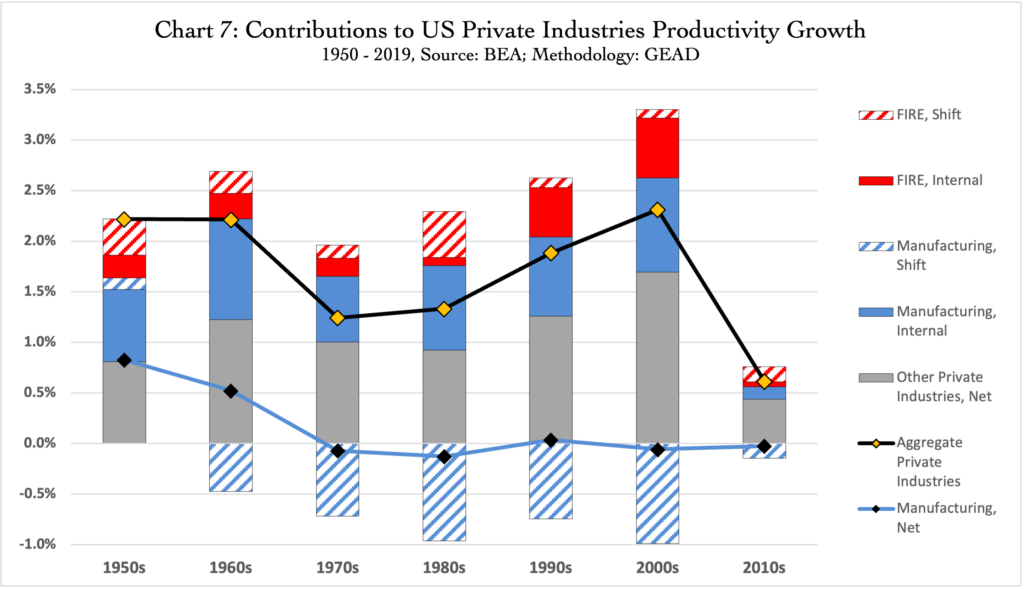

Previous charts in this series have illustrated the process of structural change in the US economy, showing the decline of manufacturing employment – both in absolute numbers and as a share of aggregate US employment – and the corresponding growth of employment in other industries (see Chart 5). Chart 6 illustrated how these structural changes moved labor resources away from the high-output, high-productivity growth manufacturing sector and into a variety of lower-output, lower-productivity growth services industries. No theory is required to explain the consequences of these changes. As a matter of arithmetic, lower productivity growth necessarily follows.

Chart 7 and this commentary build on the previous analysis to illustrate the consequences of this structural change over time and place it in historical context. The upshot: the policy-induced shift of labor resources out of the high productivity growth manufacturing sector and into a variety of lower productivity growth services industries subtracted 0.90% on average from annual productivity growth between 1980 and 2009. While reported productivity contributions from the financial sector in the 1990s and 2000s appeared to offset some of these declines, those contributions ultimately proved illusory. Instead, a toxic combination of (1) offshoring the US manufacturing sector, (2) the large trade deficits that inevitably followed, (3) the corresponding mirror image of those trade deficits in the form of ballooning domestic debt levels, and (4) a culture of “bankers gone wild,” brought on the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the Great Recession that followed.

Review of Historical Trends

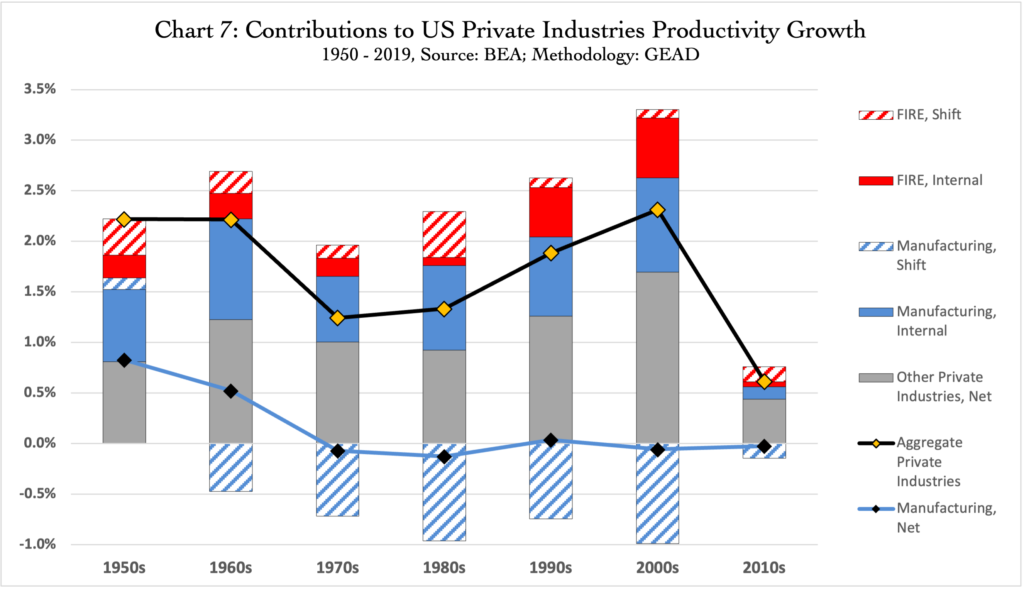

The black line in Chart 7 shows average annual productivity growth for US private industries (i.e., excluding the government sector) by decade from 1950 to 2019. The 1950s and 1960s each registered average annual productivity growth of 2.22%, which then collapsed to just 1.25% with the energy crises of the 1970s. Though often remembered as a decade of strong economic performance, productivity in the 1980s barely rebounded from the dismal 1970s, posting an average annual growth rate of just 1.33%. Productivity growth finally began to recover in the 1990s, climbing to 1.89% and then still higher in the 2000s. At 2.31%, the 2000s just edged out the ’50s and ’60s to register the highest productivity growth of the post-war period before the crash of the GFC and the Great Recession brought productivity growth down to a stunningly low average of 0.62% during the 2010s — just half that of crisis-ridden 1970s.

Prevailing explanations for the overall trajectory and volatility of US productivity growth tend to be either ad hoc or descriptive, without ever getting to a comprehensive understanding of the underlying causes. The energy and monetary policy shocks of the 1970s and early 1980s, for example, are an obvious contributing factor for the broad-based initial declines, and the IT revolution that began in the 1990s surely played some role in the subsequent recovery. But these discrete exogenous shocks, while important, are only pieces of a larger puzzle that conventional economic frameworks have struggled to explain.

The Growth Accounting Model

One common framework used by economists to analyze productivity growth is a “growth accounting model,” which seeks to parse out the contribution of labor and capital inputs to the growth of output, leaving a residual referred to as Total Factor Productivity (TFP). Delong explains this framework here (Delong on Growth Accounting) and illustrates its application to aggregate US economic performance from 1948 to 2000. Delong finds that lower capital investment helps explain the decline of productivity growth from 1973 to 1995, but the slowdown in TFP contributed even more. Unfortunately, the growth accounting model itself provides no explanation of either contributing factor, prompting Delong to explore a variety of potential underlying causes, including the oil shocks, demographics, errors in measurement, and environmental regulations. Ultimately, he concludes that “[t]he causes of the productivity slowdown remain uncertain. The productivity slowdown itself remains a mystery.”

The Techno-Pessimism Thesis

Lower capital investment is also central to another perspective on the productivity slowdown that is often associated with Robert Gordon, who has asked provocatively whether US economic growth has come to an end. Gordon identifies a number of contributing headwinds, but one common theme across his and others’ work is a faltering pace of scientific innovation and investment (Gordon 2000, Gordon 2012, Gordon 2013, and Gordon 2014). In what some have labeled the “techno-pessimism” thesis, the US economy has allegedly entered old age (Atlanta Fed 2013).

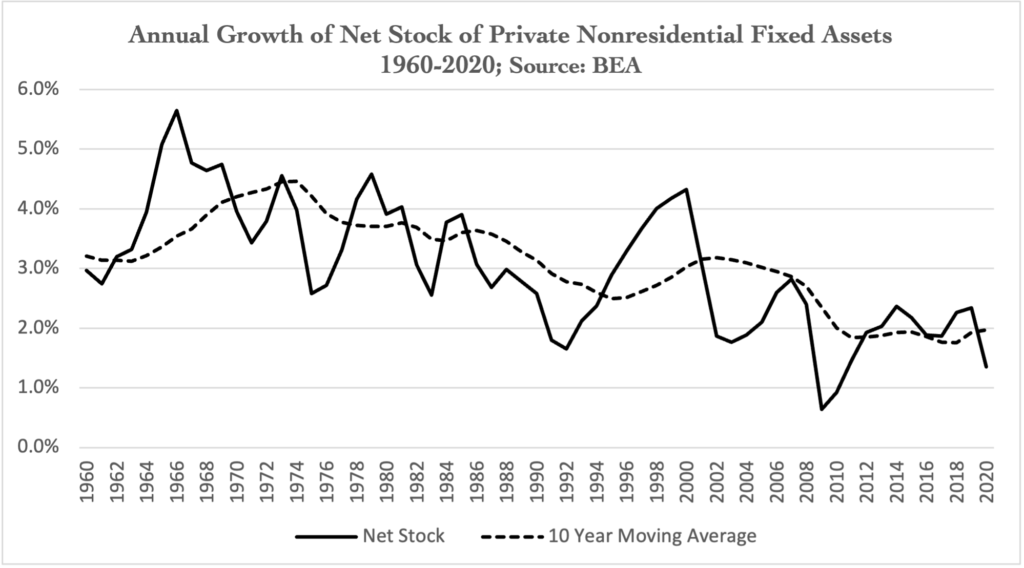

The techno-pessimists are certainly correct that the US is no longer investing in its economic future as it did in the past. As shown in the chart below, the growth rate of America’s Net Stock of Private Nonresidential Fixed Assets has steadily declined over the last five decades, and this declining trend is present in each of the three major underlying components: Structures, Equipment, and even Intellectual Property.

Yet this merely begs the question of why American business is no longer investing for the future. Have all the good investment opportunities been exploited, or is a declining rate of private investment the consequence of other factors? Short of accepting a biological metaphor that the US economy has irrevocably entered old age, how can one make sense of these wild gyrations in US productivity growth, the longer-term downtrend, the collapse of the 2010s, and all this accompanied by a sharply declining rate of capital investment?

Structural Change and Productivity Growth

Nobel prize-winning economist William Nordhaus, skeptical of the growth accounting model, pioneered an alternative explanation that places structural economic change at the center of the story. Among the shortcomings of the conventional growth accounting model, Nordhaus observes that it requires estimating the value of capital services, rather than directly measuring that value, and relies on a variety of unrealistic assumptions to do so (Nordhaus 2005; also see Nordhaus 2002). In response, and drawing on insights from William Baumol and Edward Denison, Nordhaus developed a new way of analyzing productivity that decomposed aggregate productivity growth into the contributions made by individual sectors or industries of the economy.

In a nutshell, any nation’s economy is composed of many different industries, and aggregate productivity growth can be decomposed into the productivity contributions made by each of these individual industries. Naturally, some industries achieve above-average levels of productivity and rates of productivity growth while others are below-average. Further, as labor resources migrate from one industry to another, the weighting, and hence the contribution, of the various industries changes, and with those changes aggregate productivity necessarily also changes.

The performance of a stock market index provides a useful analogy. Just as the performance of a market index is a function of the weighting and performance of the individual stocks that comprise it, so too is aggregate productivity growth a function of the individual performances of the many industries that comprise the economy. Analyzing the impact of structural economic change on productivity growth is not a substitute for considerations of exogenous shocks or other factors that affect “within industry” productivity, but structural change is a crucial, and largely neglected, dimension to a comprehensive understanding of how US productivity growth has evolved over time.

How Structural Change Impacts Productivity Growth

The contribution any individual industry or sector makes to aggregate productivity growth is a function of three factors: (1) its level of labor productivity (value-added output per unit of labor input), (2) the change of that productivity level measured over some period of time, and (3) the industry’s share of aggregate employment (or more precisely, its labor input as a share of total labor input). Many factors could impact an individual industry’s level of labor productivity and its change over time, such as improvements in the quality of labor, the quantity or quality of capital used by that labor, process improvements and knowledge gains, and changes in the composition of products and services produced.

Naturally, an industry’s share of total employment is subject to change over time. Whether due to trade, technological change, the interaction of demand and productivity growth, shifts in end-user demand, and other factors, some industries are expanding their share of the economy’s employment while others are contracting. As these labor resources move from one industry to another, the contribution they make to aggregate productivity growth changes as well.

To illustrate the impact of differing productivity levels, consider two industries that have different levels of output per unit of labor input but identical rates of productivity growth. For example, suppose industry A has value-added output per hour of $100, which increases 2% over a year to $102. Industry B has value-added output per hour of $110, which also increases 2% over a year to $112.20. A worker moving from industry A to industry B will increase aggregate productivity growth during the period the shift takes place because that worker’s value-added output per hour got an immediate 10% boost by moving to industry B. Of course, the converse is also true, moving from an industry with a higher productivity level to one with a lower level reduces aggregate labor productivity.

Now consider movement between two industries with differing productivity growth rates, which creates a potentially longer-lasting impact. If two industries have the same level of value-added output per labor hour at a given point in time but different internal productivity growth rates, then moving labor resources from the lower productivity growth industry to the higher growth industry will also improve aggregate labor productivity growth. If industries A and B in our example above both had output per labor hour of $100 at the beginning of a given year, but industry A’s output per labor hour increases 2% to $102 over the course of the year, while industry B’s increases 3% to $103, then moving labor resources to industry B during the year would increase aggregate productivity growth, as more labor resources are now employed in an industry with faster productivity growth. If these growth rate differences were persistent, the beneficial impact would be similarly persistent. Differences in industry-specific rates of productivity growth are readily apparent in the data, with slower productivity growth rates more evident in services sectors that are less conducive to capital investment and automation.

In the most beneficial scenario, labor resources would move from industries with lower productivity levels and growth rates to sectors with higher productivity levels and growth rates. Conversely, if labor resources are moving from industries with higher productivity levels and growth rates to those with lower productivity levels and growth rates, the headwinds created by this shift subtract from the contributions the high productivity sector would have otherwise made to aggregate productivity growth without being offset by equivalent gains in the low productivity job-gaining sectors. As a matter of arithmetic, aggregate productivity growth must decline.

How Structural Change Has Impacted the US Economy

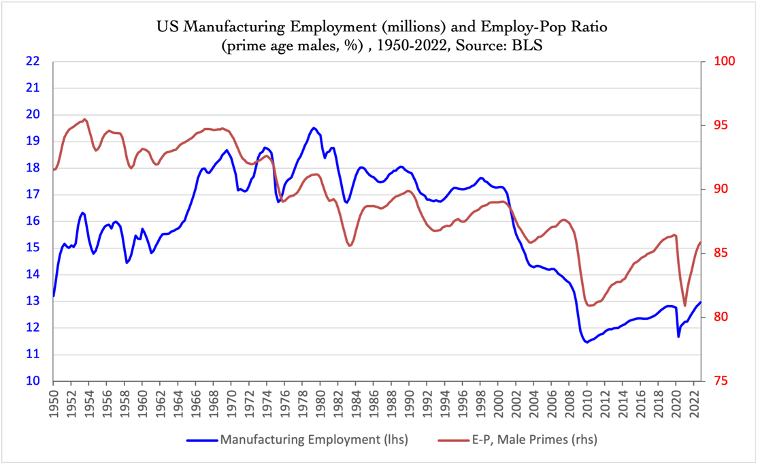

This approach to analyzing productivity growth yields great insight into how structural change, and the impact of declining manufacturing employment in particular, has weighed on US productivity growth. Manufacturing employment began to shrink as a share of total employment in the 1960s, though it was still expanding in absolute numbers and making a net positive contribution to aggregate growth. With the energy-crises that followed in the 1970s and early inroads of Asian manufacturers into the US market, absolute employment growth in manufacturing began to stall, peaking in 1979. Manufacturing employment experienced further headwinds in the 1980s as a result of the soaring value of the dollar and the growing sophistication of foreign manufacturers. Though some stabilization followed in the 1990s, the worst was yet to come.

The coup de grâce for manufacturing employment came with the US policy-decision to grant China Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR), which paved the way for its entry into the WTO in 2000. Even with an expanding economy, the industry lost more than 3.5 million jobs in the early 2000s before the GFC hit in 2008. Then, two million more job loses followed before the decade closed. All told, the first decade of the 21st century saw the loss of nearly 5.7 million manufacturing jobs, about 1/3 of the sector’s total employment.

Many of these refugees from the manufacturing sector found employment in lower-output, lower-productivity growth jobs in other sectors. But many found themselves in that least productive position of all, unemployment, and simply left the job market altogether. From 2000 to 2009 the employment rate for prime age (25 to 54) males plummeted by 8% (from 89% to 81%) as shown by the red line in the chart above.

The Productivity Drag of A Declining Manufacturing Sector

How did these declines in manufacturing employment impact US productivity growth? The bar graph in Chart 7 (shown again below for convenience) decomposes aggregate productivity growth for US Private Industries into the following five buckets for each decade: (1) the contribution of the manufacturing sector’s internal productivity growth (solid blue bar), (2) the productivity impact of labor resources shifting into or out of the manufacturing sector (stripped blue bar), (3) the contribution of the Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate (“FIRE”) sector’s internal productivity growth (solid red bar), (4) the productivity impact of labor resources shifting into or out of the FIRE sector (stripped red bar), and (5) the total contribution made by all other private industries — excluding Manufacturing and FIRE — that comprise the US Private Industries economy (gray bar).

The blue line in Chart 7 shows the net contribution of the manufacturing sector to aggregate productivity growth (its internal productivity growth adjusted for the impact of its changing share of employment), and as previously noted, the black line shows aggregate US Private Industries labor productivity growth.

On average, for the six decades from 1950 to 2009, the manufacturing sector’s internal productivity growth contributed 0.82% to aggregate US private industries productivity growth (solid blue portion of bar graph), a remarkable 46% of aggregate US Private Industries productivity growth. Yet, after accounting for the drag created by labor resources moving out of manufacturing and into lower productivity industries, the sector’s net contribution to productivity growth has been negative since the 1970s (blue line). The productivity drag created by the shift of labor resources out of manufacturing subtracted on average 0.90% of annual productivity growth and negated the entire contribution made by the sector’s internal productivity growth.

Banking on “FIRE”

Despite the productivity drag of a shrinking US manufacturing sector, aggregate productivity still rose sharply in the 1990s and 2000s as the productivity-enhancing effects of the IT revolution spread broadly across the economy. The FIRE sector, about ¾ of which is represented by employment in the Finance and Insurance industries, appeared to be especially fortunate in this regard.

In addition to expanding its share of employment, the FIRE sector experienced a remarkable surge of internal productivity growth during the 1990s and 2000s (solid red portions of the bar graph) as the combination of easy monetary policy and the IT revolution enabled its growing ranks to develop and trade a dizzying array of new financial products that promised higher returns with lower risks. And with high levels of value-add per worker, the ongoing financialization of the economy supported remarkable levels of compensation for those lucky enough to enter its citadels.

As one of the primary beneficiaries of the policy-decision to open the US market to China’s manufacturing output, the performance of the FIRE sector appeared to justify the optimistic views on globalization held by many policy-makers that America could specialize in high-value services and leave the physical manufacturing to others. Larry Summers, for example, was “banking” on such an outcome, one might say, believing that “America’s role is to feed a global economy that’s increasingly based on knowledge and services rather than on making stuff.” (link)

The 2000s were especially giddy days for the US financial sector and for American consumers. American bankers found that investors, and foreign investors in particular, had a nearly insatiable appetite for an array of US debt securities — not only Treasuries, but US agency-backed mortgage debt, and an alphabet-soup of private securitized mortgage and consumer debt.

This growing foreign demand for US debt securities was the necessary consequence of the huge US trade deficits triggered by offshoring much of the US manufacturing sector. Exports of US services simply could not balance the incredible volumes of imported goods.

Throughout the early and mid-2000s, no country ran larger trade surpluses with the US, or accumulated more US financial assets, than China. Since entering the WTO in 2000 it had begun to run massive current account surpluses in manufactured goods as a consequence of its investment and export-led economic development strategy. Recycling these surpluses into US financial assets acted as a form of seller-financing, allowing China to sustain US demand for its exports and advance its goals of industrial development and military modernization.

Of course, if the foreign sector is increasing its holdings of US financial assets, than some sector of the US economy is necessarily taking on greater indebtedness. In this case, the combination of foreign demand and “financial innovation” by the US financial sector gave American households access to immense amounts of credit on easy terms to buy houses they couldn’t afford and to borrow against the growing equity in their homes. And with homes prices spiraling upward, so long as the music kept playing it was all too easy to buy high and sell higher.

The Bust and its Aftermath

It all seemed too good to be true – and it was. While American households partied on borrowed money in the early and mid 2000s, employment in the US manufacturing sector imploded. With the burst of the credit bubble, it all unraveled, bringing the GFC and Great Recession in its wake. In hindsight, the FIRE sector’s remarkable productivity gains had reflected nothing more than its efficiency in churning out worthless securities to fuel an old-fashioned credit boom, and with it a massive housing bubble and consumption binge. The financial sector lived up to its acronym – it set the US economy on fire.

The cumulative impact of decades of structural change in the US economy came to fruition in the decade that followed the GFC. Productivity growth withered to levels not seen in the entire post-war period. The outsized contributions of the FIRE sector of past decades reversed amid broad-based declines across most industries.

The large declines in manufacturing employment of past decades subsided during the 2010s, as much of what could be offshored had already been offshored, but still the manufacturing sector made no net contribution to aggregate productivity growth because the sector’s internal productivity growth withered to less than 20% of its long-term average. Why?

The internal productivity gains posted by the manufacturing sector in the offshoring frenzy turned out to be fleeting. The national accounts do not easily distinguish between productivity gains achieved through global labor arbitrage from those achieved by improvement in domestic labor productivity (Mandel). So lower input prices are reported as increases in the value-add by domestic producers and generate short-term increases in reported labor productivity. Domestic producers were no more efficient and traded away the sustained future productivity gains that come from capital investments, process improvements, and learning-by-doing to the foreign firms doing the actual manufacturing. Moreover, US manufacturing firms, once the foundation of private sector capital investment, no longer have any reason to sustain their former rate of investment. With hindsight it is clear that the decline in the rate of US capital formation is not the root cause of declining productivity growth, but an unintended consequence of US trade policy and a declining manufacturing sector.

Conclusion

Structural economic change has structural effects. US policymakers deliberately traded away the primary engine of long-term productivity growth – the US manufacturing sector – and the American people got only financial crises and a shrinking middle class in the bargain. Even more ominous, US policy was instrumental in accelerating China’s growth into an industrial powerhouse, and with that growth has come an aggressive geopolitical competitor looking for its “place in the sun,” much like Imperial Germany 110 years ago. It would be hard to conceive of a set of policy choices more destructive to America’s economic health, unity, and national security. That these policies flowed directly from the worldview that animates much of the Washington establishment indicates an urgent need to rethink American grand strategy.