David P. Goldman, aka Spengler, recently published a short article entitled Five Myths About China, which summarizes remarks given at the National Conservatism Conference in September 2022.

Goldman is, of course, a prominent and insightful analyst of geopolitics and the global economy whose views merit serious consideration. To my reading, his rebuttal of the five myths and his policy recommendations cumulatively seem to suggest a US strategy toward China that might aptly be called (my words, not his) strategic forbearance: the US should bide its time externally – generally accepting the status quo and refraining from economic or military confrontation – while internally rebuilding the technological foundations of its military power.

An external policy of strategic forbearance contrasts markedly with that proposed by Elbridge Colby, whose Strategy of Denial advocates an immediate pivot of US military power to Asia. With the US as its cornerstone, Colby proposes assembling a coalition of US allies and partners capable of deterring a bid by China for regional hegemony. Colby sees Taiwan as the mostly likely target of Chinese aggression, which he and others believe may come sooner than expected.

Goldman rejects such measures as more liable to provoke military conflict than deter it. Rather than confront China now, militarily or economically, Goldman instead calls for an internal program to restore America’s leadership in military technology and economic innovation through federally funded R&D, investment incentives, and selective subsides, along with shifts in educational and military procurement priorities. Goldman’s recommendations for internal rejuvenation would make sense even if the US were not standing in the shadow of conflict with China.

But the focus of this post is whether Goldman’s rebuttal of the five purported myths withstands scrutiny and, following from those conclusions, how a policy of strategic forbearance affects the CCP’s calculus for war. In the discussion that follows, I argue that Goldman’s myths are in some cases not as mythological as he asserts, and that a policy of strategic forbearance may be inviting the very confrontation with China that he seeks to avoid or postpone.

Myth #1: US trade and investment are making China rich and the US can weaken China by economic de-coupling

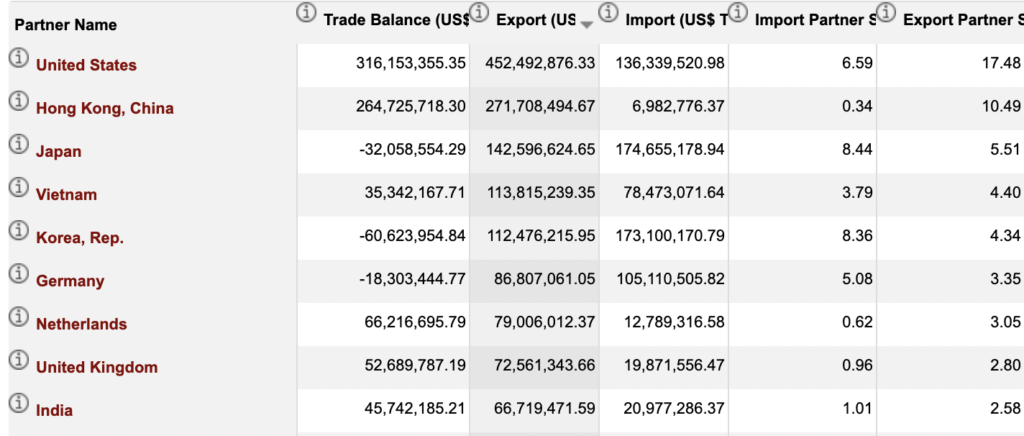

Goldman discounts the contribution of the US to China’s prosperity. In support of this he cites the diminishing contribution that US exports make to China’s GDP. He is correct that China has over time diversified its exports away from an extreme reliance on the US, and that exports to the US now account for just a few percent of China’s GDP. Nevertheless, the US is still China’s single largest export market by a wide margin, taking more than 17% of China’s exports in 2020, as shown in Figure 1 below. The next highest independent country is Japan, at less than 6%. The US is also by far the most important contributor to China’s trade surplus, providing an important boost to China’s aggregate demand. Indeed, in 2020 China’s $316B surplus with the US accounted for 61% of its aggregate $520B trade surplus (not shown in Figure 1). Further, with today’s distributed supply chains, the US is the final destination for some of China’s intermediate exports to Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, and other manufacturing exporters. The ability of these and other countries to absorb China’s exports are in part dependent on those countries’ own exports to the US.

These exports to the US, directly and indirectly, play a crucial role in sustaining China’s economic growth – especially now that China has exited its earlier period of hyper growth and continues to suffer from chronically deficient domestic consumer demand. That earlier hyper growth was driven by structural change as China shifted from an agricultural to an industrial economy. It required massive investments and generated large productivity gains, but that growth model has run its course. China’s growth is now challenged by an over-reliance on exports and especially fixed investment, some of which will never generate a return. While warnings of impending economic collapse are likely overblown, China’s economy is not healthy, and the CCP has so far resisted the difficult structural changes required, as Michael Pettis, (and here), Martin Wolf, and others have chronicled. Consequently, access to the US market, directly and through third nations, remains much more important to sustaining China’s slowing growth than a simple measure of exports as a share of GDP alone would indicate.

Further, investments and local R&D by US high-tech firms are still important sources of technological innovation and knowledge transfer. If US technology were unimportant to China, the CCP would not have such burdensome requirements on local partnering, nor would state entities continue to engage in the systematic theft of US intellectual property (the subject of Myth #2).

To be sure, the dependency runs both ways. As the pandemic and ongoing supply constraints demonstrate, the US relies on imports from China for all manner of sophisticated capital and consumer goods. The days when China supplied little more than children’s toys and textiles have long since passed. This dependency is a source of strategic leverage for China and would hinder, perhaps seriously, any sustained military response by the US to CCP adventurism (see for example, here, here, and here). Goldman sensibly recommends the US reduce this dependency by promoting the recovery of capital-intensive manufacturing. But how would such an effort affect the CCP’s calculus for war?

The irony of Goldman’s argument in Myth #1 is this: if he is correct that China’s growth and development no longer depend on the US, it creates a Gilpinian moment: the rising challenger has extracted what benefits it can from the existing system and is no longer constrained by its economic dependence on the existing hegemon – it consequently seeks to change the system rather than continue to play second fiddle. In sum, if Goldman is right that the US contributes little to China’s prosperity, then the rational choice by the CCP would be to initiate military action sooner rather than later, before Goldman’s proposed policies have tilted the balance of military power back toward the US and before the US can overcome the challenges of its supply chain dependence on China. Alternatively, if the US remains economically important to China, then a determined but measured decoupling will slow China’s economic and military progress while accelerating the on-shoring and friend-shoring of US supply chains. Of course, US efforts to economically decouple from China could also precipitate conflict, but the more likely outcome is a cold war rather than a hot one, and if China did take preemptive military action, the US would at least be better positioned to wage it than it would under a policy of strategic forbearance.

Myth #2: China depends on stolen American technology

There is no question that China has climbed the technology and knowledge ladder. Indeed, it is likely ahead of the US in some areas though still well behind in others. The CCP’s Made in China 2025 Plan is an explicit and determined effort to displace the US in one technological domain after another, initiated while US policymakers championed naïve policies that aimed to turn China into a liberal democracy. Systematic state-supported IP theft conducted by entities affiliated with the Chinese military ranks highly among the policies that contributed to this rapid pace of development. Most importantly, the theft continues on a mind-boggling scale, and it includes cutting edge technologies across a wide range of industries. Again, Goldman correctly notes that the US has to get its own house in order, investing in innovation, and the scientists and engineers that produce it, but neither can the US turn a blind eye to China’s ongoing IP theft – it is war by other means.

Myth #3: China faces demographic collapse

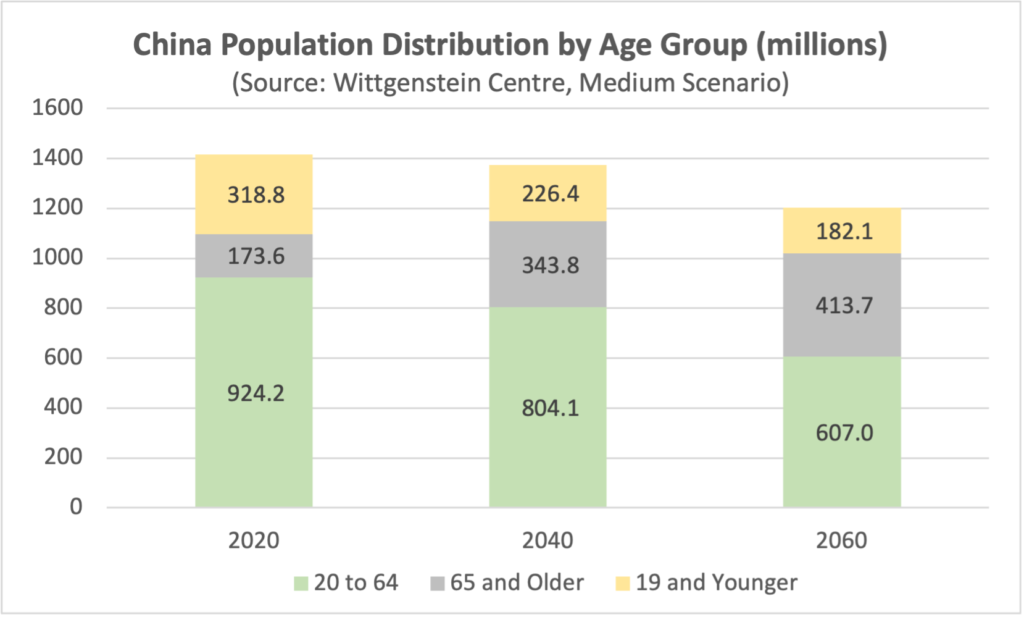

China’s working age population is expected to decline by some 10%-15% between 2020 and 2040, with even more significant declines of 25% or more in the two decades thereafter, as shown in Figure 2. Goldman is correct that some observers are overstating the near-term economic impact of this demographic decline. It won’t bring about economic collapse, but it will compound the economic challenge of China’s already deficient domestic demand – subtracting perhaps 1% annually off what is already a slowing rate of GDP growth, and with an increasing impact over time. The broader demographic decline across rich Asia and Europe will contribute further to deficient global aggregate demand and make China’s mercantilist trade policies a source of growing political conflict in the future.

“Sino-forming” the Global South, as Goldman refers to China’s initiatives to economically assimilate new markets, is not a viable long-term solution to China’s consumer demand problem, and its trading partners will find over time that a one-sided economic relationship with China does not serve their interests. The countries of the Global South seek to promote their own industrial development. Many want to emulate the earlier success of Asia’s export-led growth model, not become indebted in support of China’s need for consumer demand and trade surpluses. If China wants to economically assimilate the Global South, it will have to change its domestic political economy to a consumption-led model, something the CCP has resisted to date. So, while Goldman is correct that China’s demography will not bring about economic collapse, attempting to Sino-form the Global South will fail, leaving China struggling ever harder over time to find end-user demand to sustain its economic growth.

When China was still growing rapidly, and thereby increasing in wealth and power relative to the US, it had little reason to initiate a war for Taiwan or otherwise. But the incentives have changed now that China’s growth has slowed. If the CCP believes that military force is the only option to bring Taiwan under its control, it may come to the conclusion that it is better to do so sooner rather than later before the most serious demographic declines multiply the burdens on its already-troubled economy.

Myth #4: China’s goal to retake Taiwan is driven by ideology

Goldman downplays the Marxist-Leninist ideological component of the CCP’s goal to control Taiwan. Instead, he portrays Taiwan independence as an existential threat to the political integrity of a polyglot China – a threat over which the CCP will go to war. I do not disagree, but would add that Taiwan’s de facto independence presents a visible threat to the CCP’s claim as the sole legitimate ruler of the Chinese people. That threat must be extinguished, one way or another.

Goldman also argues, correctly in my opinion, that the CCP would much prefer to avoid war over Taiwan and take control through economic assimilation and the co-opting of Taiwanese elites. But the CCP’s actions in Hong Kong have undermined its case for peaceful reunification, and outside the KMT party, many Taiwanese increasingly see themselves as Taiwanese rather than Chinese. Would China really accept the status quo indefinitely rather than go to war, as Goldman claims? Once the potential for peaceful reunification slips away, by Goldman’s own reasoning the existential threat of an independent Taiwan would seem to increase the likelihood of military action by the CCP despite its risks. The question then becomes one of timing, driven in part by assessments of relative military advantage – which takes us to Myth 5.

Myth #5: China cannot be deterred by shifting US forces to the region

Goldman holds a pessimistic assessment of the US’ ability to deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan given the current balance of military power – or even with the redeployment of additional conventional forces. He reiterates his views regarding the impact of China’s hypersonic missile technology and its extensive anti-ship missile capabilities, the consequences of which are a point of disagreement with Colby. It is true that by some accounts and war game simulations, the US is poorly prepared to repel an invasion of Taiwan, and even in victory the US would very likely suffer major losses. Goldman further argues that an attempt to buttress Taiwan’s defenses and raise the costs of a Chinese invasion would precipitate the very attack such action sought to deter.

It very well might. But as always, the question is compared to what alternative? Even if Goldman’s recommendations were adopted today (they should but it’s highly unlikely they will), his is a long-term plan that will take many years to yield military benefits significant enough to impact the balance of power in East Asia. Meanwhile, the status quo produces a steady shift in the regional balance of power in favor of China as it fields ever greater numbers of ships and other military assets (here, here, and here for example).

As the arc of China’s relative power reaches its apogee under the status quo, perhaps some three to five years down the road, a policy of strategic forbearance becomes even more likely to produce preemptive action by China than Colby’s strategy, only the US would be even more poorly positioned to counter it. We can be sure the CCP understands power, and that they would anticipate a future adverse shift in the balance of power brought about by the policies Goldman recommends. With peaceful avenues to reunification foreclosed, there would be powerful incentives to strike Taiwan when their advantage is greatest.

Conclusion

There are no easy answers here. Goldman is surely right that the US should not provoke military conflict with China while it remains so unprepared (also here and here), and recent statements by President Biden committing to Taiwan’s defense appear imprudent. But the difference between the policy choices of strategic forbearance and Colby’s strategy of denial is significantly about perceptions of timing and military advantage: how might US policy affect the balance of military power over time, and how will that shifting balance affect the window of opportunity as perceived by China for the reunification of Taiwan by force.

Many factors suggest that window is nearer than we would like, including: (1) China’s slowing economic growth, compounded by future demographic burdens, (2) a US awakened from slumber and actively seeking to shift the balance of military and technological power back in its favor, (3) the perennial thorn and existential threat of Taiwan independence coupled with diminishing prospects for peaceful reunification, and (4) an aging Xi having consolidated his hold on power for life and eager to secure his legacy in the pantheon of Chinese leaders.

Unfortunately, the US and Taiwan may not have the luxury of time that Goldman envisions.