Key Takeaways from Chart 6 and Commentary

- In the same way that the performance of a stock market index reflects the weighting and performance of its underlying stocks, the aggregate productivity of the economy reflects the weighting and performance of the various industries that comprise it.

- The US has been losing jobs in manufacturing, a sector with extremely high productivity growth and above average value-added output per worker, and adding jobs in industries with below average productivity growth and below average value-added output per worker.

- There shouldn’t be any mystery about why the productivity growth rate of the US economy has declined – no theory is required. It is simple arithmetic that the shift of labor from high productivity manufacturing to low productivity services industries has negatively impacted aggregate US productivity growth.

- If our goal is to promote a thriving, expanding middle class, we should be moving the mix of US employment up and to the right of this chart. Instead we are moving employment down and to the left, and undermining the economic and political foundations of self-government in America in the process.

Commentary

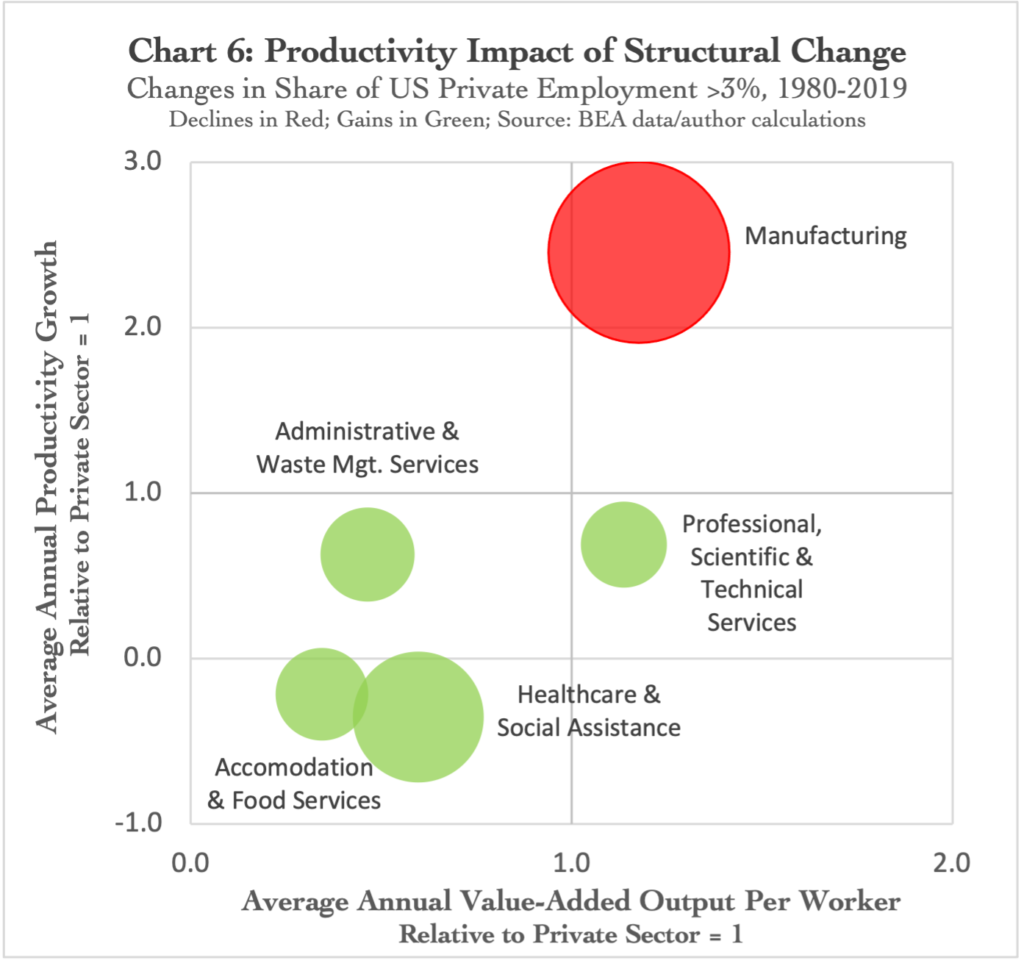

The previous chart ( Chart 5 ) illustrated the major shifts in employment across the US economy over the last five decades. The productivity impacts of these shifts are illustrated here in Chart 6. The horizontal axis shows each industry’s average annual value-added output per employee relative to the private sector average over the period from 1980 to 2019. The vertical axis shows each industry’s average annual productivity growth, also relative to the private sector average over the same period. The industry bubbles represent those industries that have experienced changes of private sector employment greater than 3% since 1980. The size of each bubble is proportionate to the change in its share of employment, with gains shown in green and losses shown in red.

By far the largest change occurred in the US manufacturing industry. From 1980 to 2019, US manufacturing employment declined from 24.3% of private employment to just 9.7%, a decline of 14.6%. In parallel with that decline, employment in several service-sector industries grew substantially. Three industries, Healthcare & Social Assistance, Accommodation & Food Services, and Administrative & Waste Management Services, grew their aggregate share of private employment from 18.2% to 33.3%, an increase of more than 15% that fully offset manufacturing’s loss of share. These three service industries now account for 1/3 of all private sector employment. A fourth services industry, Professional, Scientific & Technical Services (PST), also expanded significantly, increasing its share of private employment from 4.1% to 7.3%. This structural change in the US economy, and the massive decline of manufacturing employment in particular, is often shrugged off as the inevitable product of shifting demand patterns, or sometimes likened to the decline of agricultural employment a century ago, or explained away as the result of automation-driven productivity growth. I will evaluate these inadequate explanations in a subsequent post.

This post focuses on the productivity impact of these employment shifts. In the same way that the performance of a stock market index reflects the weighting and performance of its underlying stocks, the aggregate productivity of the economy reflects the weighting and performance of the various industries that comprise it. Because each industry has different productivity levels (more specifically, value-added output per unit of labor input) and productivity growth rates, shifting labor resources between industries also changes the weightings and contributions that each industry makes to aggregate productivity, whether for better or worse.

Let’s first consider labor shifts to industries with lower productivity levels. Suppose a worker moves from an industry with value-added output per hour of $125 and a productivity growth rate of 2% to another industry with output per hour of $100 and productivity growth rate of 2%. While both industries are posting the same productivity growth rate, the 20% reduction in that worker’s value-added output has an immediate negative impact on aggregate productivity growth during the period in which the shift takes place. Longer lasting effects are produced by labor shifts to industries with lower productivity growth. In the example above, if the worker moved from an industry with 3% productivity growth to one with 2% productivity growth, then the productivity decline would include both the negative impact from the lower level of value-added output, plus a ongoing drag of 33% lower productivity growth over time.

As Chart 6 illustrates, this is exactly what has taken place in the US. The US has been losing jobs in manufacturing, a sector with extremely high productivity growth and above average value-added output per worker, and adding jobs in industries with below average productivity growth and below average value-added output per worker. In fact, in the Healthcare & Social Services and Accommodation & Food Services industries, average annual productivity growth over the last five decades has actually been negative. The only somewhat positive shift over the last four decades is the growth of the PST industry which, though posting below average productivity growth, at least has value-added output per worker above the private sector average.

There shouldn’t be any mystery about why the productivity growth rate of the US economy has declined – no theory is required. It is simple arithmetic that the shift of labor from high productivity manufacturing to low productivity services industries has negatively impacted aggregate US productivity growth. If our goal is to promote a thriving, expanding middle class, we should be moving the mix of US employment up and to the right of this chart. Instead we are moving employment down and to the left, and undermining the economic and political foundations of self-government in America in the process.