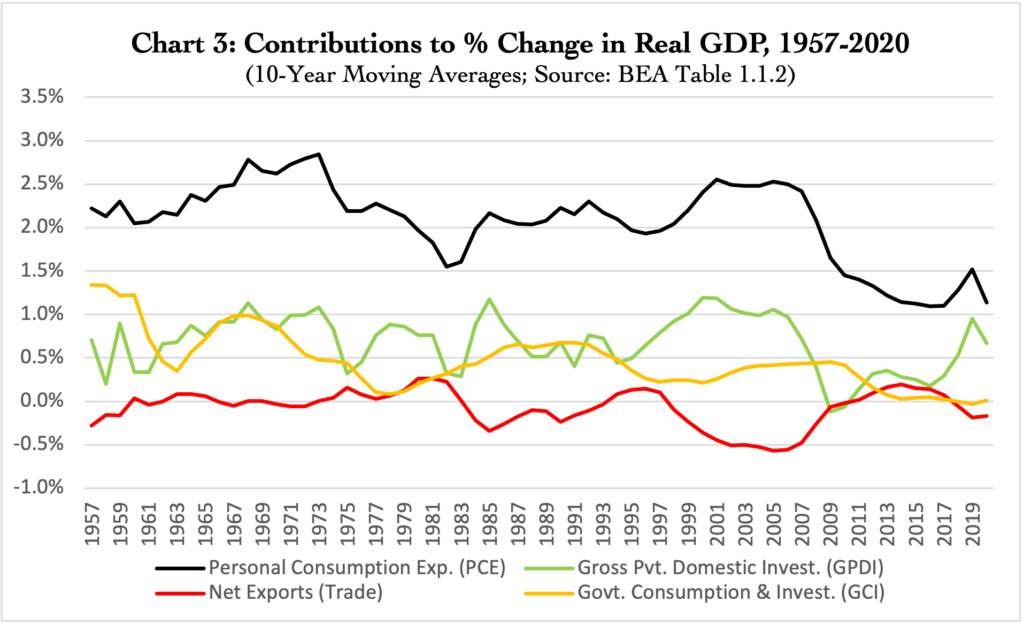

Key Points from Chart 3 and Commentary

- Net Exports (Trade) was not responsible for the strong GDP growth of the 1950s and 1960s. Since then, however, there have been periods when trade has weighed heavily on US economic performance, such as the mid 1980s, and especially from the late 1990s to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Still to be assessed is the relationship, if any, between trade and the weak productivity growth and employment rate volatility identified in Chart 2.

- Investment (GPDI) shows no obvious declines in trend contribution until the sharp fall brought on by the GFC from 2007 to 2009. However, since GPDI includes investments in residential housing along with business investment, deeper analysis is required to assess whether weak business investment buried within GPDI might be contributing to weak productivity growth.

- Elevated government (GCI) contributions to GDP prior to the 1970s primary reflect spending on national defense, but also include a significant boost from infrastructure investment and basic scientific R&D, both of which have declined markedly since then as government income redistribution programs have expanded. The impact of lower government investment, like business investment, also requires more analysis.

- Declines in personal consumption (PCE) growth largely track GDP growth, as one would expect, since household consumption ultimately depends on the growing incomes that come with growth in GDP.

Commentary

Chart 2 identified a decades-long trend of declining productivity growth and a sharp fall in the employment rate in the 2000s as the two primary drivers of the decline in US economic performance. Chart 3 begins the investigation into the root causes of these factors by examining the contributions to real GDP growth made by consumption, investment, government, and trade. These are shown as 10-year moving averages to make longer-term trends more evident. A caveat is in order: the four components of GDP are interrelated – changing one component can result in potentially offsetting changes in another. Caution is required is asserting that any particular component “caused” a corresponding change in GDP growth, but any trends evident in Chart 3 may still provide clues to help explain the weak productivity growth and the employment rate volatility identified in Chart 2.

Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE): It’s no surprise that PCE shows a declining trend – and one that is highly correlated with real GDP growth. After all, in recent decades PCE represents nearly 70% of GDP and weak consumption is ultimately driven by the same factors that drive growth in GDP and incomes. Declining growth in PCE is as much consequence as cause of weakening GDP growth.

Gross Private Domestic Investment (GPDI): Weak investment is certainly a potential cause of slow productivity growth, but GPDI contributions to GDP show no obvious weakness prior to the Global Financial Crisis. From that event GPDI declined precipitously into negative territory and only recovered slowly over the following decade. Depressed investment might be a factor in the poor economic performance of the 2010s, but at this level of aggregation, which includes residential housing along with business investment, GPDI provides no clues to explain the longer-term trend of declining GDP growth over the last five decades. We’ll need to dig deeper into the components of investment to uncover any connection to productivity growth.

Government Consumption and Investment (GCI): Note that the contributions of government spending to GDP only capture spending on products and services (whether for immediate consumption or investment), so the large increases in transfer payments since the 1960s do not add to the government sector’s contributions to GDP.

Higher than average levels of government contributions to GDP during the 1950s and 1960s primarily reflect national security spending during the Cold War, Korean War, and Vietnam War, as well as the general expansion of government at all levels. However, there is also a significant component of non-military related investment at both the Federal and State & Local levels during these years. The Federal dimension included large sums spent on the space program and other R&D initiatives. Investment spending at the State & Local level reflected large investments in infrastructure, primarily transportation related but also educational facilities for the Baby Boomers. Since peaking in the late 1960s at levels above 4% of nominal GDP (not shown in Chart 3), aggregate investment spending by the government sector has declined to levels of 2.5% to 3.0% in recent years. Whether this declining rate of government investment is related to falling rates of productivity growth requires more analysis.

Net Exports (Trade): One revealing observation from Chart 3 is the periodic headwind of trade on GDP growth rates. As a matter of economic accounting, trade deficits necessarily subtract from economic growth. Since consumption (PCE) and investment (GPDI) include spending on foreign goods and services, imports must be subtracted from GDP to avoid double-counting. When imports exceed exports, this results in a net negative impact from trade on GDP.

But assessing the true impact of these trade deficits on the US economy requires a deeper look. Trade deficits (more correctly, current account deficits) must be financed by net foreign inflows of saving, which increase the liabilities (debt) owed by the US to the foreign sector. Whether trade deficits and the corresponding inflows of saving from the foreign sector are a benefit or burden on the US economy depends on how that foreign saving is used, or more specifically, what caused the need for foreign saving in the first place: whether to fund an increase in productive investment by the business sector or higher borrowing for consumption spending by the household and/or government sectors. I will address this more explicitly in future charts using the “sectoral balances” framework, but for present purposes note that US borrowing from the foreign sector has been associated with higher consumption spending by households and government rather than increases in productive investment by business. In fact, for much of the new millennium, the business sector, far from needing foreign capital to fund its investment needs, has actually been a net lender to other sectors – an unprecedented reversal of the normal relationship in which the business sector borrows from the household sector to fund its investment. Consequently, the following discussion treats the impact of trade as a straightforward accounting exercise. Negative contributions of Net Exports to GDP growth are a burden that lowers domestic output by shifting demand from domestic producers to foreign producers, rather than a welcome forerunner of future productivity growth due to higher productive investment.

While the US exited WW2 as the preeminent industrial power amidst the destruction of Europe and Japan, the strong growth of the 1950s and 1960s was driven by domestic economic activity, not trade. Trade had a net negative impact on economic growth in the 1950s and a roughly neutral impact on average throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Shrinking trade deficits during the early 1980s created a brief positive impact, but this was followed during the mid-1980s by a deterioration in the US trade balance as the dollar soared in value against other major currencies. From 1982 to 1986, Net Exports subtracted about 0.8% from GDP growth on average, with the US trade deficit peaking at a then-remarkable -3.0% of nominal GDP. The Plaza Accord of 1985 brought dollar depreciation and with it the burden of US trade deficits slowly began to moderate. Net Exports again began to weigh on the US economy during the 1990s. For the thirteen years from 1993 to 2005 trade on average subtracted 0.5% annually from GDP growth as US trade deficits soared to nearly -6% of GDP – due primarily to soaring imports from China and the broader Asia-Pacific region.

Conclusion

Clearly, trade has weighed significantly on US economic performance at various times over the last forty years, but merely pointing out that negative impact is not an explanation. It raises more questions than answers.

- Is trade really the whole story? Some of the weakest GDP growth has occurred during times when Net Exports were less burdensome.

- What’s the relationship, if any, between trade and the weak productivity growth identified in Chart 2? After all, if domestic labor and capital resources are being freed up by trade, those resources should be reallocated to higher productivity uses, right?

- Similarly, is trade responsible for the sharp decline in the employment rate during the 2000s, also illustrated in Chart 2?

Beyond trade, what other factors does Chart 3 reveal that could contribute to weak productivity growth and employment rate declines? As discussed in the commentary, government investment has fallen from the levels of the 1950s and 1960s, so that is one factor to explore. As for business, its investment activity is aggregated with residential housing investment in GPDI, so we need parse GPDI to further assess the potential role of business investment.

Let’s dig deeper.